Update Post-Launch:

The launch of the book was a great success with the venue full to capacity, as reported by the Greek Herald on Thursday the 11th of May. The Aegis of Hellas was launched by the former Premier of Victoria, The Honourable Jeff Kennett AC. Professor Dr Michael John Osborne, Academician Professor Dr John Melville-Jones, and the President of the Greek Community of Melbourne (GCM) Bill Papastergiadis, also spoke on the night about Philhellenism, before Professor Tamis stepped on stage.

Professor Osborne’s speech, which was a highlight of the event has been published below:

Distinguished guests and colleagues:

I feel honoured to be invited to speak at the launch of such an impressive and authoritative work. As many of you will know, Professor Tamis has written numerous volumes on Hellenes in countries and regions of the Greek diaspora, but the book that is being celebrated today is surely his most significant in that it explores the nature, history and growth of Philhellenism in the world at large and reveals clearly the unique and pervasive influence that a small country has had for many centuries on a global scale.

As you will appreciate, it would be impossible to do justice to such a comprehensive study in a brief salutation, so I will restrict myself to a few pertinent observations largely concerned with the academic contributions to Philhellenism.

The chapters on the nature and growth of Philhellenism are detailed and informative, and I detect two basic manifestations, which I shall for simplicity call ‘Classical Philhellenism’ and ‘Contemporary Philhellenism’ - and I note that there can sometimes be tension between their respective objectives. By Classical Philhellenism I mean the study and appreciation of Ancient Greek society – its history, literature, art, and philosophy. As is obvious, such Philhellenism is essentially admiration for a long lost society, and some idealisation can from time to time be detected – for instance in the frequent omission of the fact that the famed democracy of Athens was based on slavery, as were most societies at the time – but I will not elaborate on this for fear of inspiring a frenzy amongst modern critics, who seek not to learn from history but to criticise the ancients for supporting such a system and , where possible, to deface or to destroy any surviving images of statesmen of the time. By Contemporary Philhellenism I mean the study of contemporary Greece, the teaching of Modern Greek language and literature and support for policies favourable to Greece. Such manifestations of Philhellenism developed strongly in and after the struggle for independence from Ottoman rule, although change did not come swiftly in the university sector – for in Oxford University, for instance, where Classics had long been available, Modern Greek was first introduced only in 1908 and endowed with a professorship of language and literature in 1915. It remains the only Modern Greek program in Britain that is the component of a BA degree.

Classical Philhellenism became prevalent in Europe from an early stage and found visibility in the writings of famous authors and philosophers, and by the 17th century in the establishment of Departments of Classics (that is, of Greek and Roman society) in most major universities. Indeed Classics became the dominant subject in universities, notably in Britain, France, and Germany, and most political luminaries, literary figures and educated persons were thoroughly imbued with knowledge of Greek history, myth, literature and philosophy. In Oxford University, a leading exponent of Classical education, there were in 1870 no less than 140 professors of Classics (as opposed to a handful in science). Such a dominance was strongly criticised by the great scientist, Thomas Huxley, in the late 19th century, but it is important to appreciate that, unlike modern critics of Classics, he was in favour of their continued presence and simply argued for greater diversity so that science and social science were not neglected. His hopes were a long time in fulfilment and it was only in the 1960s that a transformation was begun, and, as I shall note shortly, it did not take the form favoured by Huxley, and the effect has been deleterious to the Humanities.

Contemporary Philhellenism had its effective origins in and after the war for independence, and more recently it can be linked to the growth of the Hellenic diaspora. This is evident in the Orient, where Professor Tamis has thrown welcome light on the situation – and somewhat paradoxically, whereas Classical Philhellenes have been slow to develop interest in contemporary Greece, migrants have actually supported the establishment of Classical studies locally. Thus, for instance, in Beijing there are now significant university programs in Ancient Greece at Peking University and Modern Greek at the Beijing Foreign Studies University. As a professor in both institutions I can report that Hellenic Studies in Beijing are flourishing.

A somewhat different situation is observable in Australia – for, based on the British model, Classical Studies were foundation subjects in both Sydney and Melbourne universities, and only quite recently, under pressure from Philhellenes and the local Hellenic communities, have these departments expanded to offer Modern Greek. A separate chair in Modern Greek was established at Sydney in 1972, and in Melbourne in the 1990s La Trobe University took over a program initiated at the University of Melbourne and became the prime provider. With the financial support of the late Zissis Dardalis La Trobe established not just a Chair in Modern Greek but the National Centre for Hellenic Studies and Research (EKEME) with a second professor to promote Hellenism and to be the repository of the Dardalis Archive ( a unique and magnificent collection of documents, photographs and newsprint illustrating the history of the Greek diaspora, which is frequently cited by Professor Tamis in his book). The National Centre achieved international fame and was the recipient of a prestigious Alexander Onassis Award for excellence, but the fragility of such Hellenic entities was soon exposed, and it was closed in 2008 by the new university administration, and Modern Greek Studies were put in danger. Indeed in 2020 Modern Greek was scheduled for closure, only to be saved by the efforts of local Hellenes and philhellenic supporters.

There is, of course, a broader problem for Humanities here (briefly adverted to by Professor Tamis in his book). For governments (and only too many others) are increasingly disparaging of the Arts and Humanities, insisting that universities should become much more attuned to the needs of the economy and the workforce, and devote much more time to teaching and training- and this has already brought about the abolition or marginalization of many time-honoured fields of study, which inform us of the foundations and history of western civilisation. I may add that LEARNING should surely be the prime feature of a university, and teaching should only be an element of this , not a replacement.

To return to Professor Tamis’ book, he covers in impressive detail four major instances of contemporary Philhellenism, comprising reactions to the fate of the so -called Elgin marbles, the Macedonian Question, the partition of Cyprus and recent debt problems. I restrict myself to a brief comment on the first of these.

As is well known, Elgin, with the agreement of the Ottoman authorities, removed pedimental sculptures and a substantial part of the frieze from the Parthenon to Britain in the early years of the 19th century. The Parthenon was at the time serving as a mosque and it had suffered serious damage during the assault on the Akropolis by Francesco Morosini in 1687, and, according to travellers it was being mistreated by the Turks. Such at any rate was the context of ( or the pretext for ) the removal, which might possibly be characterised as a misguided manifestation of Classical Philhellenism. Elgin was in any case emulating the deeds of others who had taken antiquities out of Greece, such as the French diplomat Choiseul-Gouffier, who took part of the Parthenon frieze to Paris. Byron was deeply imbued with Hellenic scholarship, and before he visited Athens in 1811, he had contemptuously described the Elgin marbles as “Phidian freaks, mis-shapen monuments, and maimed antiques”. A few months later, when he visited Athens and viewed the Parthenon himself, he changed his mind dramatically, wrote poems violently castigating Elgin for removing the marbles and became the initiator of the campaign for their return. I can add little to Tamis’ account of this continuing campaign, but seek to emphasise that it is not a ‘return’ or ‘removal’ that should be supported, but a RE-UNIFICATION – for the marbles are PART of a great monument, and they should thus be given back as an unconditional donation.

I may add that Elginism did not die out in the face of Byron’s criticisms – for subsequently, for example, the sculptures from the Aphaia temple on Aigina were removed to Munich, and, somewhat to the embarrassment of the excavator (Alexander Conze) the massive altar of Pergamon was despatched to Berlin, where it remains today.

Throughout this book there are frequent references to the establishment of foreign schools of Classics in Athens, and there can be little doubt that these schools have stimulated greater interest in Hellenic Studies in the home countries and contributed in terms of finance and expertise to the discovery, excavation and exhibition of many archaeological sites, as well as the establishment of magnificent libraries. Originally, however, these schools were certainly introverted and they were designed to amplify knowledge of Ancient Greece – in other words they were examples of Classical Philhellenism – and they were from time to time criticised as intruders, who spent most of their efforts on excavations. In more recent times they have become more open and they cover both modern and Ancient Greece, and are of clear benefit to locals as much as to their own nationals. The first such school was established by the French in 1846, and over the years it has developed and built museums for the famous sites of Delos, Delphi and Thasos (to name but a few). Subsequently German, American and British schools were founded – and in recent times many more have appeared.

The American school has been responsible for major excavations, notably in Korinth (from 1896) and in Pylos in the Peloponnese, where Carl Blegen unearthed the Mycenaean palace of Nestor and discovered therein a hoard of Linear B tablets, dating from ca. 1500 BC and now known to be written in an early form of Greek. But perhaps most impressive has been the excavation of the ancient Agora of Athens – and herein we find an interesting dilemma over the two aspects of Philhellenism, since the Agora was regarded as ‘a national site of symbolic value’, and bringing to light the remains of the city centre of ancient Athens could only be effected by destroying the dwellings of the current residents. It had been decided as early as 1832 in the plans for Athens as the capital of Greece that the area north of the Akropolis should be reserved for eventual excavation, and in 1921 the Director of Antiquities had requested funding to commence excavations there. Negotiations for a start were protracted and complicated by the fact that the area in the 1920s was densely populated – some 300 houses catering for more than 5000 persons, many of them refugees from the Smyrna debacle of 1922. The cost of expropriation of properties was well beyond the resources of the Greek government, and after much diplomatic manoeuvring and political agitation the American School secured permission to undertake the excavation at American expense and on the condition that all antiquities should remain in Athens. In the 1950s, of course, the area was made the more magnificent by the reconstruction of the huge Stoa of Attalos (built in the second century BC and wrecked by the Heruli in 267 AD) – the enormous cost being borne by wealthy American Philhellenes. Excavations are, of course, still in progress.

The British School, which adjoins the American School, began operations in 1886, and in the late 1960s its director, Peter Fraser, who was not just a fine scholar but in every sense a Philhellene (having served with the Greek resistance throughout the Second World War) set an important example by being the first to open up membership of the School to scholars and students from countries with no such base in Greece. Many Australians took advantage of this opportunity to become members until in 1980 the Australian Institute was founded by Alexander Cambitoglou.

Enough! I have already become a victim of the dictum that ‘no speech can be long enough for the speaker, or short enough for the audience’, and I will desist. But one final sentiment – this book deserves the widest circulation and readership as an authoritative account of the continuing vigour of Philhellenism and Professor Tamis deserves our sincerest congratulations and thanks.

Further details about the event can be found at the link provided: ‘Fundamental study of Philhellenism’: Professor Tamis’ latest book launched in Melbourne – Greek Herald

Pre-Launch Background:

On the 10th of May 2023, a book launch will be held for the book titled “The Aegis of Hellas: The Continuing Vigour of Philhellenism”, authored by Prof. Dr Anastasios M. Tamis and published by the Hellenic Parliament Foundation. In it’s media release about the book, the Hellenic Parliament Foundation stated the following:

“This is an overview and analysis of the multiple forms of interest in Greek culture – from ancient times until the present day all over the world. The book considers not only the Hellenic Diaspora but also the various cultural networks consisting of people who study Greek civilization as a form of cultural reference. Each chapter of the book discusses a continent, and refers to people, legacies and processes that were, and remain active, in the specific time and geographical space.

Clearly, the scale of this research endeavour is massive. It is a step towards a global overview of Greek cultural references. It embraces academic work, journalism, economic, political and social actors, popular and high culture. It focuses on the concept of networks, a prominent feature of the organization of the Greek world and of philhellenism for centuries. It stands as a testimony to the resilience, vigour, contemporaneity and radiance of Greek culture and of the communities of the Greek Diaspora. On the other hand, it examines this radiance as one of the many factors that shape the contemporary world and seeks to place the influence of global Greek culture and legacies in their proper contexts, geographical and historical.

The Hellenic Parliament Foundation hopes that this work will contribute to the ongoing discussion about the role of culture, transnational movements and especially philhellenism in the shaping of the contemporary world. Moreover, the Hellenic Parliament Foundation presents this publication as an expression of its profound respect for the numerous people throughout the globe – Greeks by descent, but also (so many of them) Greeks by choice – who either dedicate their lives to the study of Greek culture or take an active interest in it as a cultural reference. In a world that moves at breathtaking speeds, and in an era in which constant change is the order of the day, the activity, contribution, work and impact of these people are a great honour for the whole of the Greek nation. This book is also an expression of gratitude for the Greeks of the Diaspora – one of them is the author of the book – who carry their cultural legacies in their hearts. These cultural legacies help them become active and creative citizens of their new homelands. On the other hand, this book is not simply a discussion of legacies only; the reader will also note that it addresses the present and offers food for thought for the future as well.

This book is also about culture and ethos (paedeia); it aims to validate that culture also includes such all-significant matters as language, philosophy, politics, science, art, literature, and religion, as well as mental and moral activities which, more than the outcomes of a material nature, determine the course of civilization. The roots of civilization, being the product of man’s creative activity, lie deep in the ages gone by. Naturally, the Hellenic culture, ethos and civilization in diachronia, over the last 3,500 years, during its persistent creative capacity, have been adopted by non-Greeks to satisfy their social, cultural, political, and other needs. They can be described as philhellenes.

The Hellenic Parliament Foundation as well as the author are aware that the subject of this book is so wide that it could not possibly aspire to settle the issue in a definite manner. It is, however, an attempt to sketch a comprehensive picture of global philhellenism and provide a reference work. Both the Foundation and the author hope that this book may become the pivot for the better understanding of the global connotations of Greek culture, but also for the undertaking of additional studies about them.”

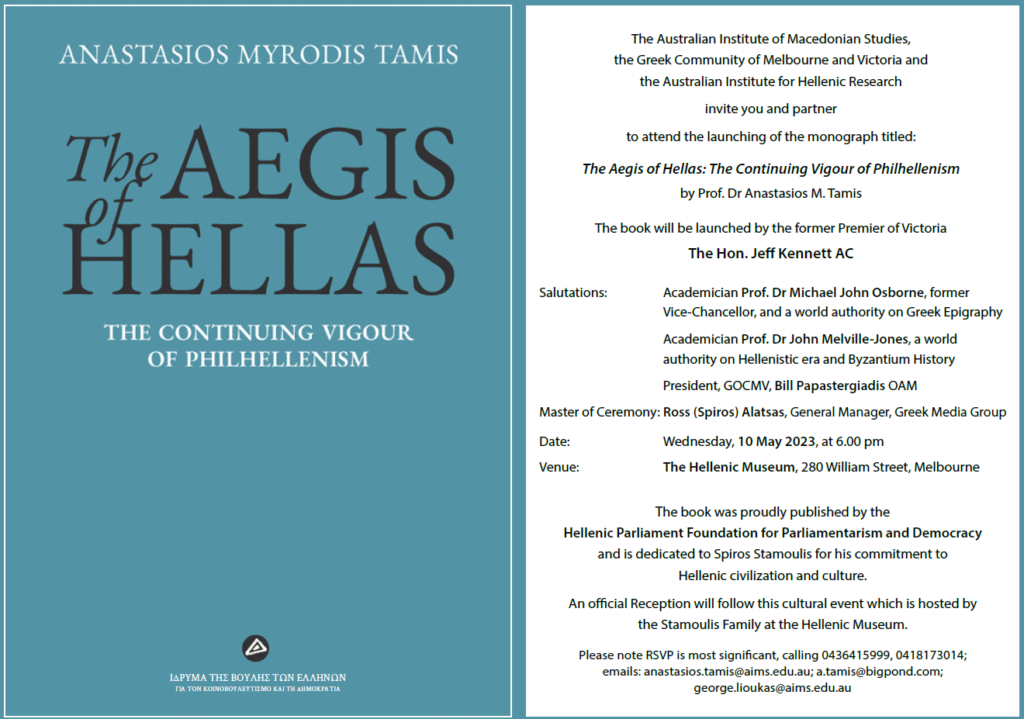

The book will be launched by the former Premier of Victoria, the Hon. Jeff Kennett AC. The event will take place at the Hellenic Museum in Melbourne. Details of the event are shown in the invitation below. Note that places to this event are limited and attendance is only by RSVP.

An article about the book and the book launch event was published in the Greek Herald on the 19th of April 2023. The article can be found below and can be downloaded as a PDF.

6 Comments

Anomymous · 4 May 2023 at 7:41 pm

At this time it sounds like Expression Engine is the top

blogging platform out there right now. (from what I’ve read) Is that what you are using

on your blog?

George · 6 May 2023 at 12:12 pm

No, we do not use that as a CMS.

Anomymous · 30 May 2023 at 9:22 pm

Wow, wonderful blog layout! How long have you been blogging for?

you made blogging look easy. The overall look of your site is excellent, as well as the content!

Anomymous · 31 August 2023 at 11:23 am

I stumbled upon this I have found It positively useful and it has aided me out loads.

Anomymous · 15 September 2023 at 3:50 pm

Thank you for the good writeup.

Anomymous · 26 September 2023 at 5:12 am

I’ve been exploring for any high quality articles or weblog posts in this kind of space. Exploring in Yahoo I finally stumbled upon this web site. Studying this info I’m glad to express that I have found out exactly what I needed. I will make certain to not overlook this web site in future.